A do-over by the Justice Department

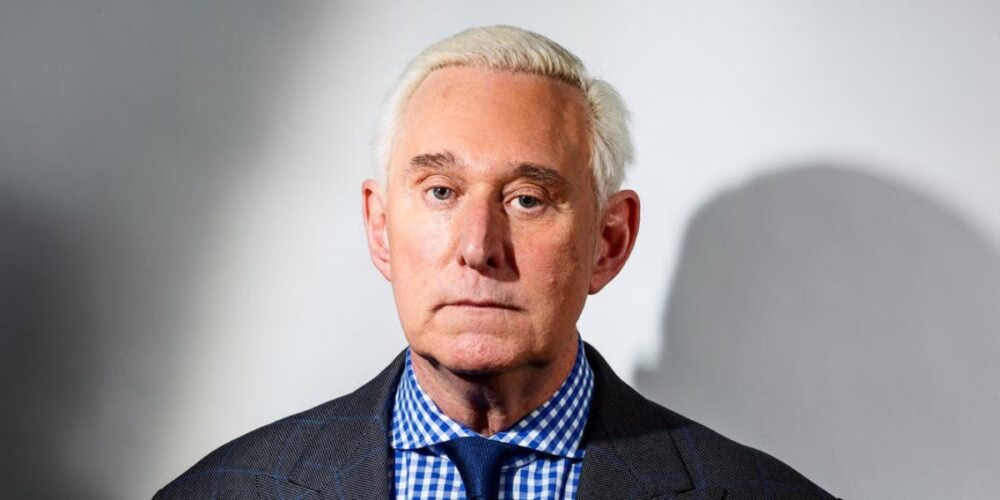

The impartial administration of justice is key to the practice of democracy. Just what “impartial” looks like, however, is being severely tested this week. Last year, Roger Stone – a close friend of President Trump – was convicted of various crimes, including interfering with witnesses and lying to investigators seeking to uncover the details of Russian interference in the 2016 election. Prosecutors had recommended a prison sentence of between 7 and 9 years for Mr. Stone. However, in a highly unusual move, the Justice Department, acting through Attorney General William Barr, substituted the recommendation of the prosecutors for a more lenient – albeit unspecified – sentence, leading to the withdrawal of all the prosecutors from the case.

- Did the Justice Department break the law? No. The Attorney General has the power to overrule a prosecutor. If the Attorney General was acting on the orders of, say, the President, the overruling would still be legal. The Justice Department is an element of the executive branch of government, which is led by the President, and so is required to implement all lawful policies determined by the President.

- So…what’s wrong then? Preserving trust and order in society requires more than following the rules. As a matter of policy – not law – the Department of Justice has long acknowledged that it needs to be seen to do justice, and be seen to do justice – and not be regarded as a vehicle for political machinations.

- Why might this be political, and not simply a reversal of a considered legal position? When the prosecutors filed their original recommendation, they correctly noted that it was “consistent with applicable advisory guidelines” on sentencing for the crimes concerned. Given the high profile nature of the case, it seems almost inconceivable that their superiors in the Department of Justice were unaware of the recommendation. Yet, the following day, the Justice Department overruled its prosecutors – overruled itself, in other words – and argued that the advisory guidelines were inappropriate and instead “defers to the Court as to what specific sentence is appropriate…”

Echoes of the past

Synagogues attacked, a politician murdered, a far-right party’s favored candidate gaining the governorship of a state. Those are the headlines of 1930s Germany. Sadly, they are also the headlines of 2020 Germany. For 14 years, Chancellor Angela Merkel has led Germany with skill. But, all reigns come to an end. Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer was, until last week, Merkel’s favored successor. Then, however, a local chapter of Merkel and Kramp-Karrenbauer’s party, the Christian Democrats, allied themselves with Germany’s far-right party, the Alternative for Germany (AfD), in electing a right-wing governor for the state of Thuringia. That was a vote in defiance of the stated policy of the Christian Democrats not to cooperate with the AfD, and exposed Kramp-Karrenbauer’s tenuous standing in the party. A few days later, she stepped down as the party’s candidate to succeed Merkel.

- Is there really a historical parallel? Yes. Thuringia was the first state in which the Nazis won power. Noting this, the editorial of the influential German periodical Der Spiegel reflected “the conservatives of the Weimar Republic thought they could use Hitler. In truth, he was using them…they were in the final stage of democracy’s demise without even realizing it.” Of course, Germany of 2020 is a profoundly different country to Germany of 1930, so the comparison is imperfect. But, human behavior is timeless, so a look at the past can’t hurt.

- Why are Germans rejecting the democratic gains they made under the capable leadership of Angela Merkel? Merkel’s highly effective management of the economy – particularly during the Eurozone crisis that threatened the Euro currency – made her exceptionally popular with the public. But, higher elevations lead to longer falls. In 2015, Merkel’s principled stance in favor of accepting refugees saw over a million migrants entering Germany. After isolated violent incidents involving migrants were highly publicized, their presence became anathema to a significant portion of Germans, directly leading to the rise of the far right AfD. Moreover, the AfD took root most firmly in the forgotten and economically marginalized eastern parts of Germany, offering nationalist nostalgia to woo voters feeling alien in their own land.

Democracies stand a better chance of not getting sick

Loyal readers might remember that in our newsletter of January 9th, 2020 we highlighted a study in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet, which found that an increase in a country’s democratic experience had a direct and positive effect on reducing mortality from both non-communicable and communicable diseases. Let’s hope that still holds true, because we have a new communicable disease on our hands. The global effects of the coronavirus epidemic, COVID-19, are devastating. Following the outbreak in Wuhan, more than 42,000 cases of coronavirus have been confirmed in China, 1,000 of those being fatal. Beyond its borders, 24 countries have reported almost 400 cases, with a single fatality. However, coronavirus is sure to spread further, and national public health systems are readying to contain it.

- Has China’s political structure compromised its ability to fight coronavirus? Yes. The authoritarian nature of China’s government allows it to – more or less – ride roughshod over its citizens. It might be assumed that this regimented control allows the government to secure its public in times of public health emergencies. As coronavirus is proving, however, this is not necessarily the case. Authoritarian regimes place a premium on controlling the flow of information. When an alert doctor, Li Wenliang, tried to warn the government of an emerging new virus late last year, Li was detained by police for the crime of “seriously disrupting the social order.” His warning was ignored. After his release, he returned to work, fighting coronavirus on the frontlines. Sadly, he contracted the virus shortly thereafter and died on February 7th. For a country accustomed to being censored and kept in line, the anger expressed online has been both widespread and deep. The Chinese government’s reticence with information also caused two further, larger problems. First, it enacted a travel lockdown of unprecedented scope, preventing some 11 million people from leaving Wuhan. However, because the government had delayed its response, 5 million people – that is to say, nearly half – left Wuhan of their own accord immediately before the travel restriction. Second, experts are concerned that such blanket bans (rather than targeting identified infected persons for care) could lead to food shortages, violence, and cause people to flee – so having the opposite effect of a quarantine.

- What are democracies doing differently? A lot. Good public health practice – and good democracy practice – seeks to keep a society functioning as normally as possible at all times. Information is pushed out rapidly to allow people to take self-protective measures. Mandatory quarantines are deployed only as a last resort and made against identified carriers of an infectious disease or those with a high likelihood of carrying it. Britain and France – both of which have identified coronavirus on their shores – have adopted this approach. The United States began by screening all arrivals from China, with only those bearing coronavirus symptoms being sent for further care and treatment in isolation. This targeted approach has subsequently been replaced by stricter measures, barring entry into the United States by any foreign national who has travelled to China within 14 days. All US citizens returning home from China are to be quarantined for 14 days. These restrictions have been criticized by both public health experts and civil liberties advocates as being overly broad – but are still narrower than those adopted by China.

Local NoCal News

Read your local newspaper lately? Thought not. For some years now, local journalism has suffered tremendously as local newspapers across the country have closed down. With it goes the ability of residents of a town to learn facts relevant to the fabric of their lives and to share their ideas in dialogue with each other. But, every now and then, a good story comes along, a story of salvation.

Downieville lies in Gold Rush Country, California, founded by seekers of fortune and glory. Fortune and glory have long since moved on but, for a time in the 1850s, it was a boomtown. Boomtowns make news, and so the Mountain Messenger was dutifully created. As California’s oldest weekly newspaper, it counts Mark Twain as one of its early column writers. Sadly, with deteriorating revenues, the Mountain Messenger recently looked to be on its way out. History, though, had not reckoned with the arrival of Carl Butz.

Retired, and at a loss after the sad passing of his wife, Butz channel-hopped one night, settling on Citizen Kane, that great Orson Welles drama about a wealthy newspaper publisher. Butz thought “I can do that!” And he did, buying the Mountain Messenger for a tiny sum and throwing his considerable energies into it. It is early days, but Butz and his sole journalist, Jill Tahija, have made every deadline yet.

- Great! What can I do to help? Carl and Jill are thriving. But your local paper might not be. Local papers tell the stories of your community. If there aren’t stories being told, there isn’t a social fabric being woven. So, once you’ve finished reading, why don’t you start writing for your local? Many local newspapers don’t have an online presence, so it is best to look in your local store or coffee shop for copies and to find out how you can volunteer.