Congress recently passed the (mostly) bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act, pumping $52 billion into domestic semiconductor production and more than $200 billion into science and technology research. It’s a good sign that we’re taking semiconductor production seriously, and a few years ago it would be cause for celebration. Unfortunately, it still falls short.

Right now, Chinese warships are surrounding Taiwan, the world’s most advanced producer of semiconductors. CCP outlets promise that “solving the Taiwan question will only be a matter of time in the next few years,” while China is decades into a deliberate plan to shore up domestic semiconductor production and turn itself into the global leader.

This isn’t competition as usual. As the global leader in semiconductor production, China could shape the future of tech development, and when it has had the power to do so in the past, things haven’t exactly turned out well for the free world. China is the world leader in artificial intelligence, facial recognition, and surveillance technology, which it promptly combined into a nationwide panopticon that it is exporting around the world.

And with every passing day, a Chinese invasion of Taiwan seems less a matter of if than when. When it happens, the Free World will be at a loss. Taiwanese semiconductor production will collapse as suddenly as the Ukrainian agriculture industry, and with even greater global consequences.

Semiconductors are a niche subject, but they’re not something we can afford to ignore.

What Doesn’t Need a Semiconductor?

From smartphones, to computers, cars, home appliances, military systems and life-saving medical devices, semiconductors are fundamental to modern electronics. They constitute the key element of a computer chip, so the words are often used interchangeably in politics.

At the moment, democracies dominate semiconductor production. Taiwan is the world leader in actually producing chips, but countries in the Free World take part in every step of production. The Netherlands builds the fabrication machines, American and Japanese companies design the chips and specialized equipment, South Korea manufactures them, and the United Kingdom and Germany are critical members of the global supply chain. Meanwhile export controls enforced by the US and its democratic partners lock China out of the tech necessary for the most advanced manufacturing.

The Threat of Invasion

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s Tuesday trip to Taiwan is a reminder just how serious China is about conquering Taiwan.

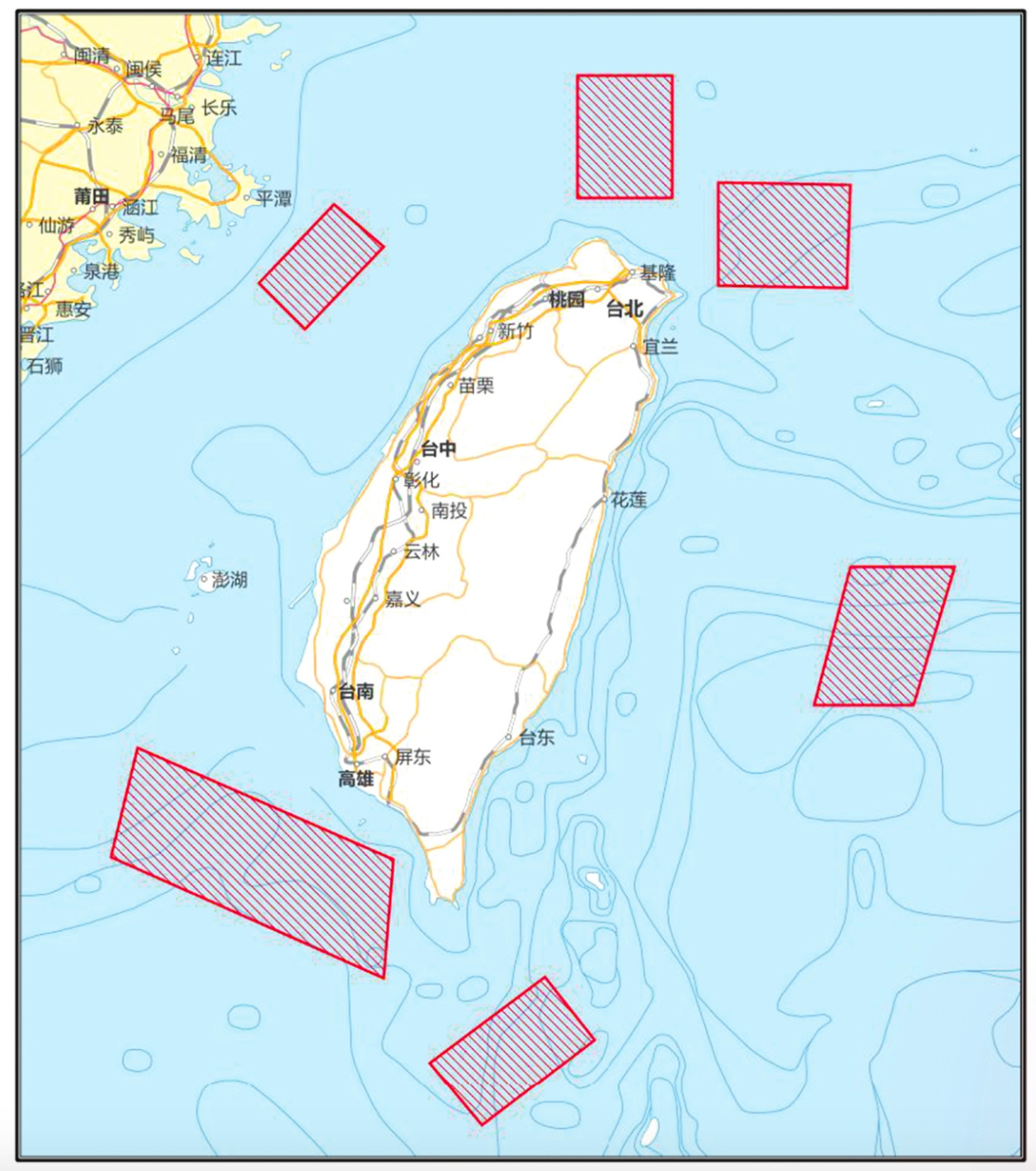

As the military jet carrying Pelosi touched down in Taipei, Chinese ships moved into position around the island. At six locations, they will conduct live fire drills from Thursday, August 4 to Sunday, August 7th as a show of force. The Chinese are unlikely to invade at this moment, but they insist that it’s only a matter of time.

The island nation is at the center of a seven-decade-old dispute regarding the legitimate government of China. In 1949, China was embroiled in a civil war between the communists and the Kuomintang nationalist party. The communists under Mao won the mainland, and the Kuomintang fled to Taiwan. Ever since, Taiwan has governed itself and slowly developed a national identity independent from China. According to public opinion polling, 89.9 percent of Taiwanese consider themselves Taiwanese alone, rather than Chinese or a mix of both identities.

But China has never given up on its dream of “reunification” (even though, it’s worth noting, the CCP has never actually ruled Taiwan). Were China to invade, it would destroy Taiwan’s semiconductor production in the short term. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has foundries located along the island’s west coast, facing China, and built in cities close to the shore. Some were constructed less than 12km from so-called “red beaches,” areas that are likely landing sites for a Chinese invasion. Were China to attack Taiwan, these foundries would likely be damaged or completely destroyed, severing the supply of advanced semiconductors to both the US and China.

According to TSMC Chair Mark Liu, “Nobody can control TSMC by force. If you take a military force or invasion, you will render TSMC factory not operable. Because this is such a sophisticated manufacturing facility, it depends on real-time connection with the outside world, with Europe, with Japan, with US, from materials to chemicals to spare parts to engineering software and diagnosis.”

If there’s a silver lining here, it’s that China also depends on Taiwanese semiconductors and would damage its own economy by reclaiming the island. That thought offers little comfort, though, for the Taiwanese. As the Russian invasion of Ukraine demonstrates, extending borders and affirming national pride can triumph over practical concerns like international popularity and economics. The Chinese government has sworn for so long that it will capture Taiwan, it’s difficult to believe they would change course.

For the US and the rest of the world, the risks are extreme. Without Taiwanese semiconductors, global electronics production would be crippled.

China’s Rise

Even barring an invasion of Taiwan, the US’s prospects of challenging China’s rise in semiconductor production are limited. China has spent decades nurturing its semiconductor industry, ever since 1956 when the Chinese State Council introduced an Outline for Science and Technology Development named semiconductor technology a “key priority.”

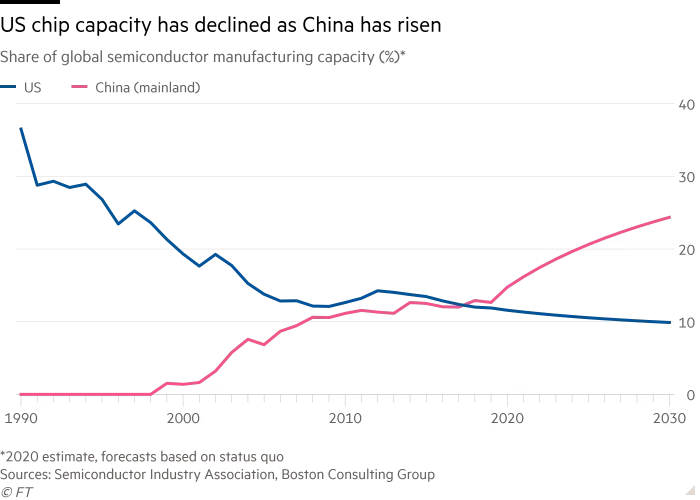

The Chinese have only become more serious since then. Chinese president Xi Jinping’s “Made in China 2025” investment initiative calls for China to become a world leader in semiconductor design and manufacturing. China is projected to lead the world in semiconductor manufacturing by 2030. This is largely due to government incentives and subsidies, which have helped make construction of new fabrication plants in China 37-50 percent cheaper than in the US.

Need for Stronger US Action

While the US was the birthplace of semiconductors, its manufacturing industry has stagnated. America’s share of global microchip production cratered from 39 percent in 1990 to 12 percent in 2019. To cut costs, US companies like Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) and Nvidia decided to specialize in chip design while offshoring manufacturing to companies like the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

The CHIPS Act is a step in the right direction to address this vulnerability, but it is insufficient. Compared to China’s gargantuan $1.4 trillion investment plan in their homegrown semiconductor industry, America’s $52 billion CHIPS Act is a drop in the bucket. If we’re serious about defending American interests and resisting the rise of an autocratic nation dominating the tech sector, CHIPS is just a starting point.

To really compete with China, we need to ensure that we recruit the best minds to join in production and design. As the Bloomberg editorial board noted, around 40 percent of the high-skilled semiconductor workforce is foreign born, and though we’re educating more and more immigrants in our top graduate programs than ever before, we’re making it exceedingly difficult for these people to get visas and make their career in the US. We are already struggling to fill jobs in chip production, and an influx of new investment will exacerbate that problem without changes to our immigration policy.

Second, we need to bolster our industry without leaning into the twin evils of protectionism and stagnation. Critics of the CHIPS Act are quick to point out that these subsidies risk turning our industry complacent, fat off subsidies rather than competing to make the best product. It’s a legitimate concern, but China has successfully fueled its semiconductor industry growth and the risk of not trying is worse. Encouraging competition and allowing companies to recruit the international expertise they need will go a long way in making this happen.

Meanwhile we should aim to strengthen American industry without cutting ourselves off from the world. The United States is not going to be able to replace international semiconductor production, nor would that be desirable. The Taiwanese aren’t just the largest semiconductor producers, they’re also the best. European companies provide critical research and components that the US should welcome into our supply chain. Self-sufficiency in the US market would rely on restricting trade rather than just funding new developments, and would ultimately be self-defeating.

And finally, we should do everything in our power to dissuade a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, both as a practical matter and as a matter of principle. Threats help, but arming Taiwan is better. The Chinese have cause to be skeptical of our willingness to go to war with another nuclear superpower. It’s Taiwan’s strength that could properly intimidate China, and it’s our responsibility to help them defend themselves.