On Monday, it will be a year since Hamas terrorists crossed over the Gaza border into Israel where they killed nearly 1,200 people and took over 200 hostages.

Mere hours after the attack, Russia, China, and Iran began planting the seeds for a coordinated disinformation campaign, setting up accounts across online networks to profess support for Hamas and deepen divisions in the democratic world. Meanwhile, rallies decrying Israel filled the streets of open societies before Israel even had a chance to muster a response.

The eagerness of those living in democracies to apologize for and even celebrate Hamas’ atrocities was bewildering to many. But to those who have been paying attention, it was entirely unsurprising.

The enemies of open societies have been increasingly collaborating across borders. The past year has unfortunately confirmed that the barriers between domestic and foreign threats are becoming more porous. None of this is happening by accident.

Whether we want to admit it or not, we are at war. According to Constantine Nicolaidis and Catherine Terranova—two experts who are working to define this new domain of warfare—the nature of the battlefield has changed.

I spoke with Nicolaidis and Terranova this week to make sense of the shifting storm of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda hanging over America in the aftermath of October 7.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity and concision.

_____________________

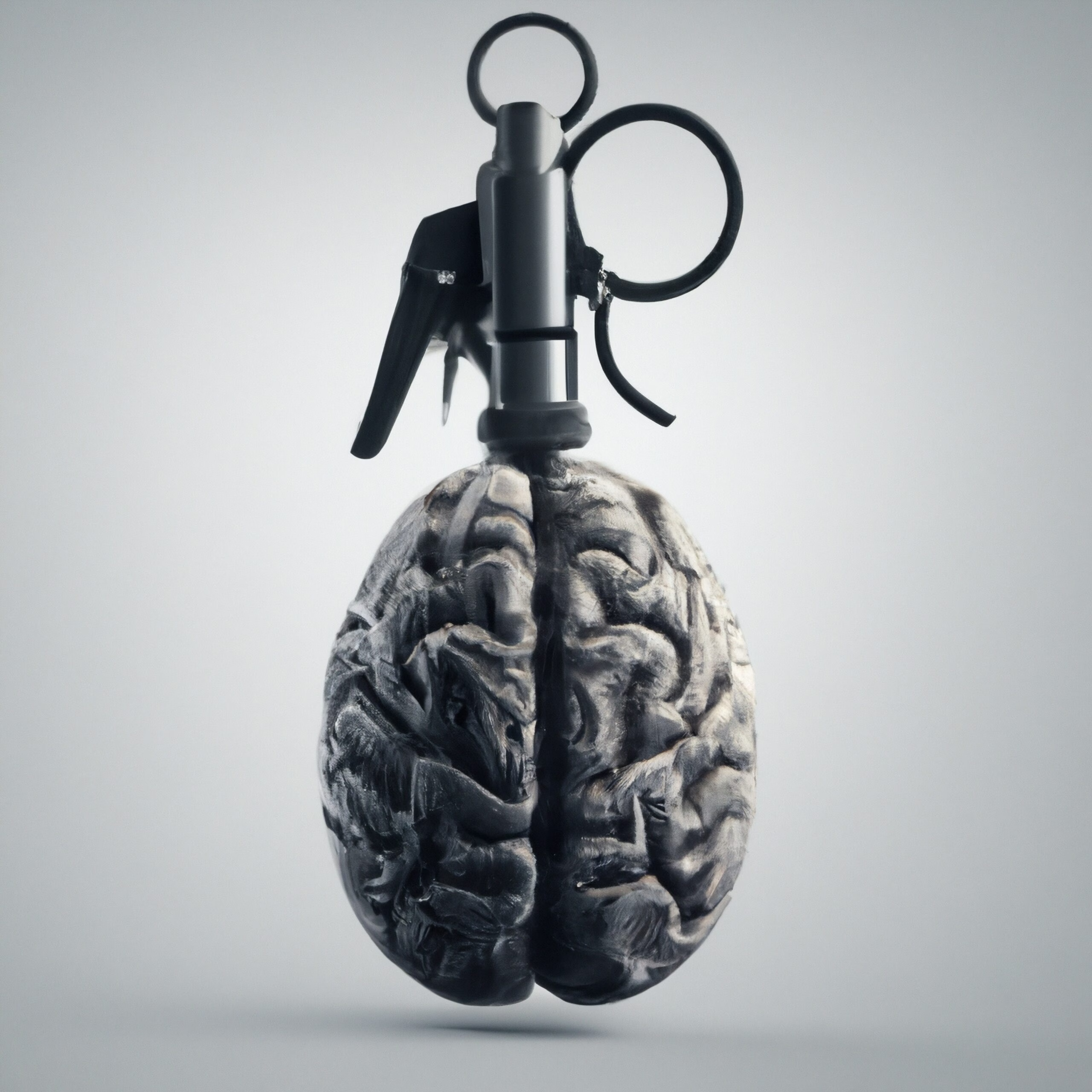

Mewada: What is cognitive warfare?

Nicolaidis: Cognitive warfare is a new way of attacking a population. This domain includes a lot of things like the traditional concept of psychological warfare or notions of propaganda and influence. Those are all in there. But it recognizes that those areas have become an entirely new domain of warfare—like air, land, and sea.

The advent of social media and the whole attention economy around algorithms has fundamentally changed the game. Cognitive warfare ends up being larger than just misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda. We now know a lot more about how to manipulate the human brain. And we’re all now directly wired into the internet, via our mobile phones and computers—devices that offer a straight shot into the brain.

Cognitive warfare hacks individual minds in order to disrupt an entire country by targeting an entire political system. Liberal democratic societies are much more vulnerable to those attacks. It has emerged as a major method of degrading democracy around the world.

Mewada: So what are those vulnerabilities, and who are the main actors exploiting them?

Nicolaidis: Under current conditions, it’s important to understand that certain of our elites have become radicalized to the point where they want to break our own system. This typically happens on both the Left and the Right.

The term Peter Turchin uses for this is “counter-elite.” Tucker Carlson, many people have observed, has moved increasingly in a radical direction with his politics. Turchin points to Carlson in his book as a textbook example of a counter-elite. So once you have become an American counter-elite, at this point you are also an internal threat actor in a liberal democracy.

And so traditionally speaking, these counter-elites almost always team up with foreign actors that are also trying to break the system, whether explicitly or implicitly. Because in the realm of cognitive warfare, the far-left and far-right are essentially in cahoots with the foreign actors that are attacking our system. It’s very much the case that Russia, China, and Iran are very interested in waging cognitive war and spending billions of dollars doing it. But they’re getting help from internally radicalized far-left and far-right elites.

Another factor that makes us vulnerable is our norms surrounding the freedom of information and speech. Let’s look at a classic tactic that’s used in cognitive warfare—the repetition of information. A lot of cognitive warfare involves injecting information into open societies, and getting people to repeat it. The moment that information is repeated, it has been laundered. At that point it’s protected by free speech. So our free speech is used against us as a method of preventing us from just pointing at something and saying, “That’s a lie,” and then taking it away.

Mewada: What do cognitive warfare campaigns look like?

Nicolaidis: Cognitive war campaigns have a couple key characteristics. A campaign typically seeks to make the population feel or think a certain way. It repeats key narratives through various channels, in an effort to influence its targets. If you think about Americans who don’t believe in democracy anymore—some of that’s natural, but some of that’s been inflamed.

Trying to undermine our notion that democracy is functioning is a common theme in these campaigns. I think the Russians first invented this concept. During the Cold War, there was an idea that Russia would try to show that communism was superior to the liberal democracy. Now, it seems that the Russian strategy is just to degrade our belief in democracy, so that our population doesn’t see the difference between an authoritarian and democratic system. This is explicitly stated within their doctrine. It’s not like we are interpreting these things. If you look at some of the originators and some of the early fathers of cognitive warfare in Russia, they’re explicitly talking about this.

Our political system makes it such that you have a really easy time believing damning information when it is blamed on the other side. We are split in the United States between Democrats and Republicans. People will identify strongly with either the Left or the Right. So you can talk to Democrats all day about Russian misinformation and they will just nod their heads and agree. And then when you start pointing out information from both Russia and China that’s manipulating the Left, they are shocked by it. The political spectrum is almost at this point just being used to trick America and divide it.

Because part of the trick is that anybody to the left of center is as crazy as the craziest figure to the far-left. And anybody to the right of center is just as crazy as the craziest figure to the far- right. And so that’s not actually how our population splits out what they think and how they feel, but everybody believes the craziness as long as it’s on the other side of the political spectrum. And so they’re not seeing the true, core centrist qualities of the general population on both the Left and the Right.

Mewada: We’re nearing the one year anniversary of the October 7 attacks on Israel. How did these dynamics play out in the domain of cognitive warfare after those attacks?

Nicolaidis: There’s a lot of symmetry going on here that is worth unpacking. We are going into an election cycle. A third of our country believes the last one was stolen. That was an intentional campaign by a group in the country with somewhat counter-elite tendencies being reinforced by the foreign actors. A third of our country thinks the last election was stolen. And we have two proxy wars happening right now.

We have two democratic allied countries—Ukraine and Israel— that are at war. We now have two radicalized portions of our population in the millions who both are on opposite sides of the spectrum and believe we shouldn’t be supporting one or the other of our proxies in this war. That is cognitive warfare happening in real time. None of that is naturally occurring.

It is not a mystery if you are watching Russian and Chinese accounts where the narratives are coming from. If you knew where to look on October 7, it was just like a blitzkrieg on these accounts. Russia and China had the same accounts all together at the same time. We tracked these accounts, we know what they’re saying, and it all happened exactly in coordination with the attack. We even knew some of the American accounts that were either fake accounts or trolls. Organizations that themselves have been clearly co-opted by Russian and Chinese actors were all basically humming to the same tune within 12 hours of the initial October 7 invasion before Israel had a chance to respond.

The cognitive warfare attack, which was a combined arms operation between Russia, China, and Iran, happened nearly simultaneously with the October 7 attacks. Now, can I explain how they coordinated that? No, but I know it happened at the same time because I watched it happen in real-time.

Terranova: Adversaries like Russia are really good at planting seeds and then watering them and watching them grow. There was an explosion of misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda networks that ranged from being pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian, or pro-Ukraine and pro-Russia. These networks were as polarized as you can get, but they were just dumping accounts from both sides of the spectrum to confuse and polarize the population. And that was five years ago.

The Black Lives Matter movement is another example where foreign adversaries started planting seeds and transplanting narratives that had to do with Israel and Palestine. But there’s a reason why they’re trying to spread all of these narratives and polarize people, because once something actually happens like a proxy war in the Middle East, you then have a population that’s been embedded with tons of propaganda so that they suddenly have an opinion on this proxy war that is probably going to be vastly different from their neighbor’s opinion. And now suddenly, we’re all on two sides of the fence on an issue that few people had thought about before 2020, unless they’re an adult who had lived through some of the conflict.

Even non-profit structures in America are being exploited. For example, some victims of the October 7 attack are suing Students for Justice in Palestine and American Muslims for Palestine because the Anti-Terrorism Act in America allows you to sue foreign adversaries or terrorist organizations if there’s a non-profit in America that’s funneling money to that terrorist organization. There was a young guy named David Boim who was killed in the West Bank by Hamas terrorists. And so his parents sued certain non-profits that were funneling money to Hamas.

The Boims’ case was one of the biggest anti-terrorism cases in American history. His parents won $150 million, but could not collect it because that organization shut down and refurbished itself as American Muslims for Palestine, which is currently a big force behind all of these campus encampments, handing out the pamphlets and teaching tactics.

Iran is also obfuscating their ties to all these nonprofit organizations that are funneling money to Hamas. Russia obfuscates all of who owns their companies by having all these Russian nesting doll companies where one company owns another company, which owns another company, and so on. Then there’s China, where people still wonder what the TikTok threat is, despite it being owned by a foreign adversary.

Nicolaidis: TikTok featured prominently in the October 7 cognitive warfare attack on the US population. And you could see that by looking at certain influencers. It was particularly effective in the music and fashion world, which is dominated by the Left.

They had clearly tweaked their algorithm to target certain groups. So those influencers would see an inordinate amount of collateral damage. 90 percent of their feed would be collateral damage. And then they would start seeing content about how their own country was untrustworthy, and that the politicians they were supposed to trust—which are the Democrats if you’re on the Left—were the ones perpetuating this “genocide.” Then they start mixing in some of the antisemitic tropes, saying the news is controlled by the Jews and therefore untrustworthy too.

And what’s interesting is that in the targeted population, you would see influencers that were not in any way politically engaged. They were selling fashion accessories, and all of a sudden they had the strongest beliefs about the war in the Middle East. And when they reposted extremist content talking about being pro-Hamas—not pro-Palestinian, pro-Hamas—they would explode in popularity.

Mewada: How can democracies like the US—and open societies in general—defend against those kinds of attacks?

Terranova: It is important for people in free societies to increase their awareness of the sources and narratives they are consuming and be able to identify who is trying to make them think certain ideas, whether it be Iran, Russia, or China.

They should understanding of what the forecast is going to be for foreign disinformation and propaganda—just like the weather. You can’t stop the rain, but if you know it’s going to rain beforehand, you can certainly bring an umbrella. And so we want to give people the cognitive umbrella that they need to not get drenched by all of these narratives and themes.

Nicolaidis: Cognitive attacks mix together truth and lies. So the idea of trying to come in and catch all the lies or filter them out is a horrible tactic. If you try to adjudicate the truth, you’re playing into their hands. People in free societies must be aware of the source of these narratives and be able to identify who is trying to make them think certain ideas.

We won’t get far telling people what to believe, but we can inform them that some people who don’t have the best of intentions for our democratic system really want you to believe certain things. That is way more powerful than trying to tell people what to think.

Sohan Mewada is an associate editor at the Renew Democracy Initiative.

Constantine Nicolaidas is principal of user research at Carnevale Interactive and has previously spoken on geopolitics, cyberthreats, and building organizational resilience at DEFCON.

Catherine Terranova is the executive director of the Voting Village, where she focuses on cyber security and election integrity with an emphasis on misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation.