In 1990, the writer Mario Vargas Llosa, representing an establishment center-right party, was defeated in the second round of the Peruvian presidential election by Alberto Fujimori, a right-wing populist. During his decade in power, Fujimori embraced authoritarianism, shutting down Congress, suspending the constitution, and purging independent judges. He commanded death squads to crush the Maoist Shining Path insurgency, and orchestrated the mass sterilization of more than 200,000 people, mostly indigenous women.

Two decades later, Alberto Fujimori’s daughter Keiko became a presidential contender. Vargas Llosa warned in 2010 that a return of the Fujimori family would be “a real catastrophe” for Peru, maybe leading to another dictatorship. Then last month, Vargas Llosa announced that “Peruvians should vote for Keiko Fujimori” in the June 6th presidential election.

It was a stunning reversal, but neither he nor Fujimori had changed their beliefs in the slightest. Vargas Llosa still thinks that Fujimori would rule as a dictator, but he considers her challenger, Pedro Castillo, to be an even worse prospect. In Vargas Llosa’s words, Fujimori “represents the lesser evil and with her in power, there are more possibilities of saving our democracy, while with Pedro Castillo I don’t see any.”

As of June 9, Castillo is the apparent winner of the election with 50.2% of the vote versus Fujimori’s 49.8%.

Who are Fujimori and Castillo?

There were only two faces on Peruvian ballots Sunday, and both were frightening options.

On the right was Keiko Fujimori, who pledged to bring “demodura” or “hard democracy” to Peru, emulating her father’s “dictablanda” or “soft dictatorship.” She spent 16 months in jail during 2019 and 2020 on money laundering allegations, and promised to free her father––imprisoned for human rights violations––if she’s elected.

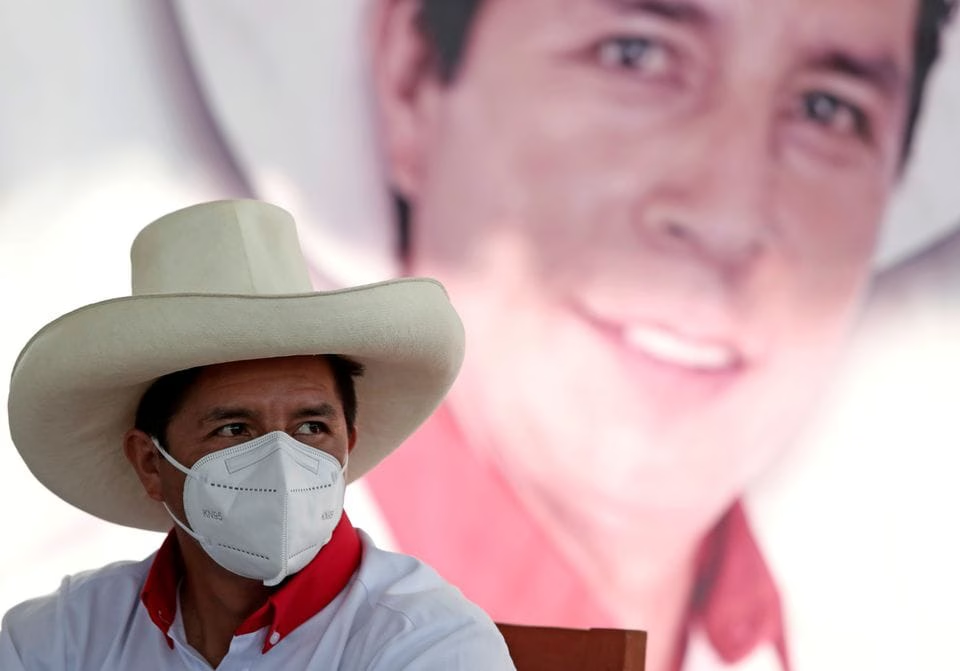

On the left side of the ballot was Pedro Castillo, a candidate so obscure that when he won the first round of elections, CNN coverage substituted a silhouettefor a photo of him. Castillo is a 51-year-old school teacher and union leader with a populist, renegade image and ties to leftist militia groups. Campaigning from horseback with a cowboy hat, Castillo has promised to nationalize Peruvian industries, rewrite the three-decades-old constitution, and dissolve Congress if it stands in the way of his agenda.

Why are Peruvian politics so extreme?

It seems that Peruvians are getting more and more fed up with corrupt rulers.

Five consecutive presidents from 2001 to 2020 were convicted or investigated on corruption charges. As of November 2020, 68 lawmakers were under investigation for alleged crimes. No wonder, then, that 94% of Peruvian citizens believe that corruption in their country is “high” or “very high.”

To make things worse, the pandemic has absolutely devastated Peru. Poverty and unemployment spiked; the underfunded healthcare system collapsed; children weren’t allowed into their schools. A horrific one of every 200 people died either directly from COVID or as a result of inadequate healthcare.

Amid these overlapping crises, Peruvians still went to the polls in April of this year to vote for a new president. A crowded field of 18 candidates, widespread disillusionment with politics, and a nation in decline brought about a perfect storm. Radicals Castillo and Fujimori emerged as the two candidates going to the runoff despite their historic unpopularity. Castillo only captured 19% of the vote, and Fujimori just 13%. Their combined 32% share of the electorate is the lowest for any two frontrunners in the past 40 years.

After the runoff elections this past Sunday, the public doesn’t seem any more united on a direction for the country. Castillo is almost certain to win by just tenths of one percent.

What do the Peruvian elections tell us about democracy?

Peru is a warning about democratic disillusionment. Democracy became a vehicle for theft, and voters lost faith. More people submitted null or empty ballots than voted for Fujimori in the first round of the election (2 million vs. 1.86 million), apparently feeling like none of the 18 candidates could improve Peru. The ultimate result was an election with two dreadful options: a likely left-wing dictator or a likely right-wing dictator.

As democratic societies across the world are racked with rhetoric questioning the legitimacy of free elections and vilifying opponents as enemies of the state, that necessary faith is tumbling everywhere. Only about 30% of Americans born in the 1980s believe that it is essential to live in a democracy, so there is every reason to think that disillusionment and extremist candidates might become our own perennial issue if we can’t make a change.