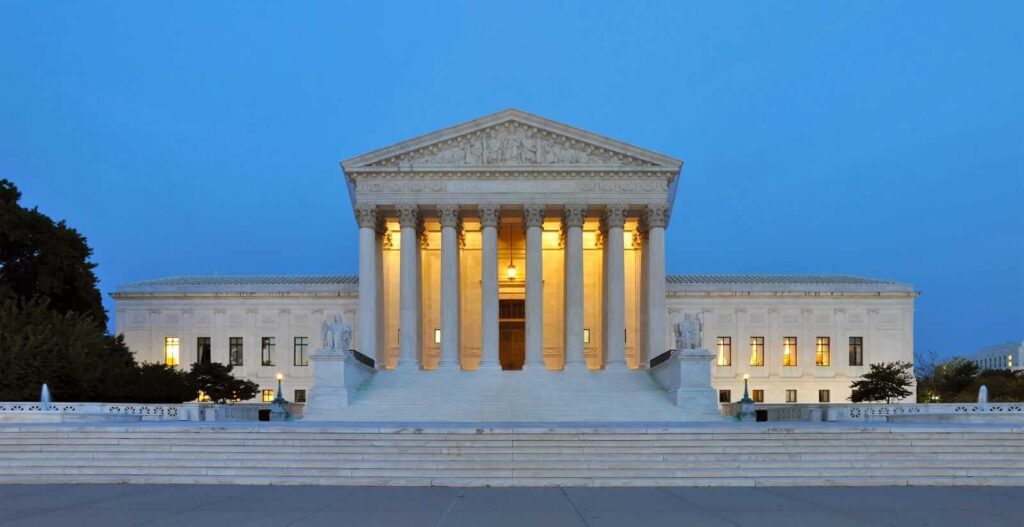

The Supreme Court seemed ready to reject a fringe legal theory supported by far-right Republicans to restrict judicial review of state election laws, enable gerrymandering, and potentially even create a route to overturn election results. Former judge J. Michael Luttig described it as “the single most important case for American democracy since the founding of the nation.”

Now it looks like the Supreme Court’s opportunity to reject the radical theory may have slipped by.

The case in question, Moore v. Harper, originated from a debate over electoral maps in North Carolina. In February 2022 the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the Republican legislature’s severely gerrymandered maps violated the state constitution. Republican leaders appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case. After oral arguments in December, the Supreme Court was expected to make a decision soon.

Then last Friday the North Carolina Supreme Court, now with a Republican majority, reversed its position and determined that the gerrymander was legally sound and the court had limited jurisdiction to rule on it anyway. With the North Carolina Supreme Court and legislature no longer in conflict, the Moore v. Harper case is in limbo. It’s unclear whether the Supreme Court will make a decision at all after North Carolina’s reversal.

The circumstances reek of partisanship. North Carolina’s move appears to be a last-minute effort to save the gerrymander––and the legal theory behind it––from facing scrutiny by a Supreme Court that signaled its skepticism. The process has further threatened the political independence of the judiciary and cast a lifeline to a radical theory threatening American democracy.

Independent State Legislature Theory and North Carolina

The Republican legislature’s case relies on Independent State Legislature Theory, a fringe reading of the Constitution which holds that state courts have essentially no power to check the constitutionality of state election laws.

“[Independent State Legislature Theory is] inconsistent with the practices of state legislatures and state constitutions in 1787, and it’s flouting 100 years of clear precedent from 1916 all the way to 2019,” legal scholar Vikram David Amar told CNN. Nevertheless, when the Supreme Court agreed to hear Moore v. Harper last year it seemed that the Supreme Court might end up supporting the idea. The reaction from the legal community was overwhelming with liberals and conservatives aligning against it.

The mood changed in December after the case came before the Supreme Court for oral arguments. While Judges Gorsuch, Alito, and Thomas seemed supportive of aspects of Independent State Legislature Theory, the other three conservatives appeared more skeptical. Judge J. Michael Luttig wrote that “it was clear the Supreme Court has no appetite for the independent state legislature theory.”

North Carolina Republicans, having taken the case to the Supreme Court with hopes of winning endorsement for the theory, were watching their maneuver backfire. But conditions had changed in North Carolina since February 2022, creating an opportunity to keep the gerrymandering and the fringe idea intact.

The North Carolina Supreme Court is an apolitical body, but the path to winning a seat on the court is overtly partisan. Judges are elected by the public after running campaigns like any other politician, and in 2022 two seats were available. On Election Day the two Republican candidates defeated their Democratic rivals, flipping the composition of the court from majority Democrat to majority Republican.

Now with a Republican majority, the North Carolina Supreme Court decided to relitigate the February 2022 proceedings in a case called Harper v. Hall. Last Friday the court announced its decision: the February 2022 decision is reversed, meaning that there is no longer any conflict between the state court and the state legislature.

Yesterday the North Carolina Supreme Court delivered a letter to Supreme Court Clerk Scott Harris regarding Moore v. Harper ”to notify the Court that on Friday, April 28, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court issued the attached decision in Harper v. Hall.” The message from North Carolina to the Supreme Court is clear: the case is moot, so don’t pursue it any further.

Protecting Against Election Interference

With a Moore v. Harper decision no longer a guarantee, extreme gerrymandering in North Carolina is back. Operating under court-imposed maps in 2022, Republicans and Democrats evenly split North Carolina’s 14 congressional seats seven to seven. Now Republicans are likely to adopt a map at least as extreme as the one the court shot down in 2022, which would have seen Republicans win 10 or 11 seats to Democrats’ three or four.

More dangerously, Independent State Legislature Theory may go unchecked by the Supreme Court. That would set us up for a frightening situation in 2024 where the constitutionality of election laws may be decided close to the elections, leading to untold chaos and accusations of partisanship. But even if the court determines it won’t continue with Moore v. Harper, it doesn’t have to be that way.

As legal theorists Vikram David Amar and Jason Mazzone wrote earlier this week, the Supreme Court can immediately agree to review Huffman v. Neiman, a case out of Ohio that also touches on the core ideas of Independent State Legislature Theory. If the court expedites proceedings, it could come to a decision this fall leaving a year of runway before the 2024 elections.

The importance of getting this right is enormous. “Never before have federal elections been under such intense litigation pressure; resolving theories like [Independent State Legislature] in as calm an environment as possible is of paramount importance,” Mazzone and Amar continued.

2024 is bound to be controversial. The Supreme Court could go a long way in avoiding controversy and crisis by hearing a case on Independent State Legislature Theory this year. The last thing we need is to head into election season with little idea about the constitutionality of the most explosive idea in electoral law.