Well, it depends who you ask.

Ask Senator Ted Cruz and he would explain that it’s a mode of thought which holds that “America is fundamentally racist, that all white people are racists” and “that whites and blacks hate each other and have to hate each other.”

Turn on PBS last week and you’d hear Judy Woodruff describe it as simply “a way of thinking about America’s past and present by looking at the role of systemic racism.”

More accurately, Critical Race Theory is an academic concept originating in the late 1970s and early ‘80s among legal scholars. Gary Peller, a Critical Race Theorist and law professor at Georgetown, described it as “the diverse work of a small group of scholars who write about the shortcomings of conventional civil rights approaches to understanding and transforming racial power in American society…. Even law students find the ideas challenging.”

That is Critical Race Theory. It’s complicated, nuanced, and academic. But public officials have politicized the concept, intentionally lied about what it is, and distorted the definition so much that the pursuit of truth becomes impossible.

How is the meaning of “CRT” driving division?

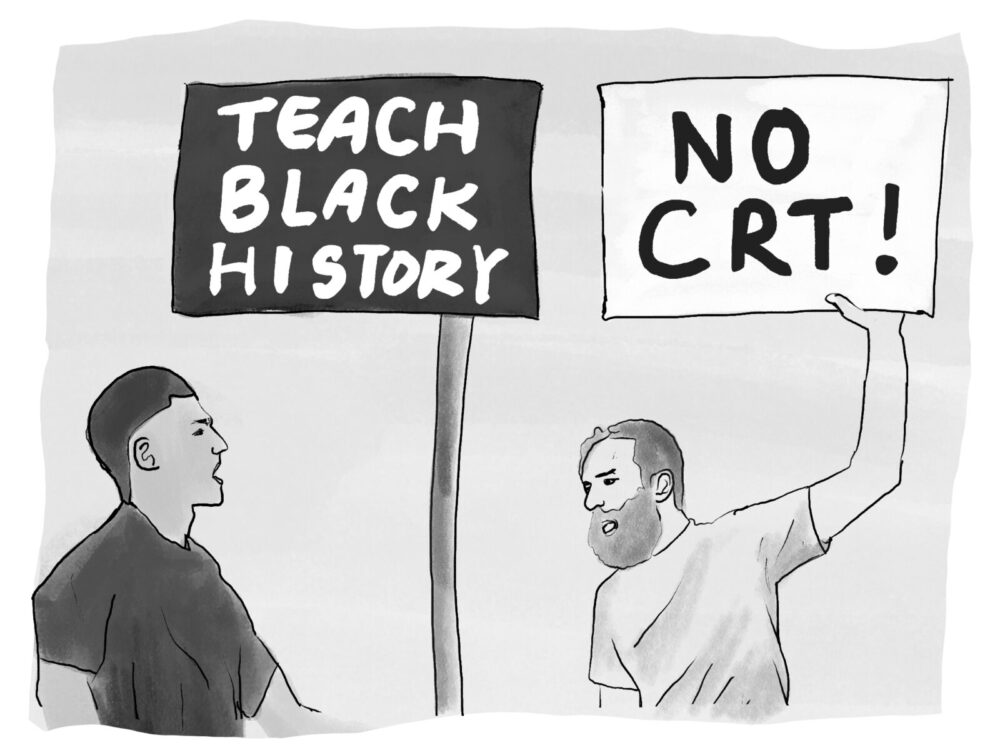

Since partisans can’t agree on a single definition, each side talks past the other. When a progressive Democrat and a conservative Republican talk about critical race theory, they are talking about two different things entirely.

Imagine a politician says they support Critical Race Theory. To someone who learned the term from Fox News, that politician just went on the record in support of telling white schoolchildren that they are the irredeemable beneficiaries and perpetrators of racism. A CNN viewer, on the other hand, might walk away believing that the politician was only suggesting that we should acknowledge the enduring legacy of racism in America.

One could go even further and imagine a debate between two people who both believe that this legacy should be taught in schools, but that schools shouldn’t go so far as to teach everything through the lens of oppressor and oppressed. These two people actually agree on substance, but if they have wildly different definitions of Critical Race Theory, they could find themselves completely at odds.

Our national discourse suffers when words take on different meanings for different people, making it more difficult to find common ground and compromise.

How do we move forward?

Both sides should be willing to give an inch. The Left should relegate terms like Critical Race Theory to the college classroom where they originated. Defending the term itself, rather than shifting the conversation to concrete action, is self-defeating. It should also avoid the patronizing, reductionist rhetoric of some ‘antiracists’ like Robin DiAngelo; and acknowledge that some leading historiansdo dispute certain elements of the 1619 Project.

Meanwhile, the Right should stop calling everything it doesn’t like “Critical Race Theory.” Their efforts to resist all curricular changes in schools, even when necessary, are clearly in bad faith. Almost half of Americans don’t believe that the Civil War was fought over slavery, and many have never heard of the Tulsa Race Massacre. That’s a serious problem.

Though verbal tussles tend to be superfluous, the CRT culture war is already causing harm well beyond bedlam at suburban school board meetings. Right-wing legislatures are passing vaguely-written laws which may make engaging with fundamental aspects of American history illegal. Ed Week reports that teachers in Idaho, Iowa, Oklahoma, and Tennessee could have to avoid discussing Jim Crow or risk violating these laws.

With our nation’s communal ties increasingly stretched, we should focus less on debating arcane academic terms and more on making changes that will help Americans of all backgrounds understand and empathize with one another. Everyone would be better off for it, especially those from historically marginalized groups.